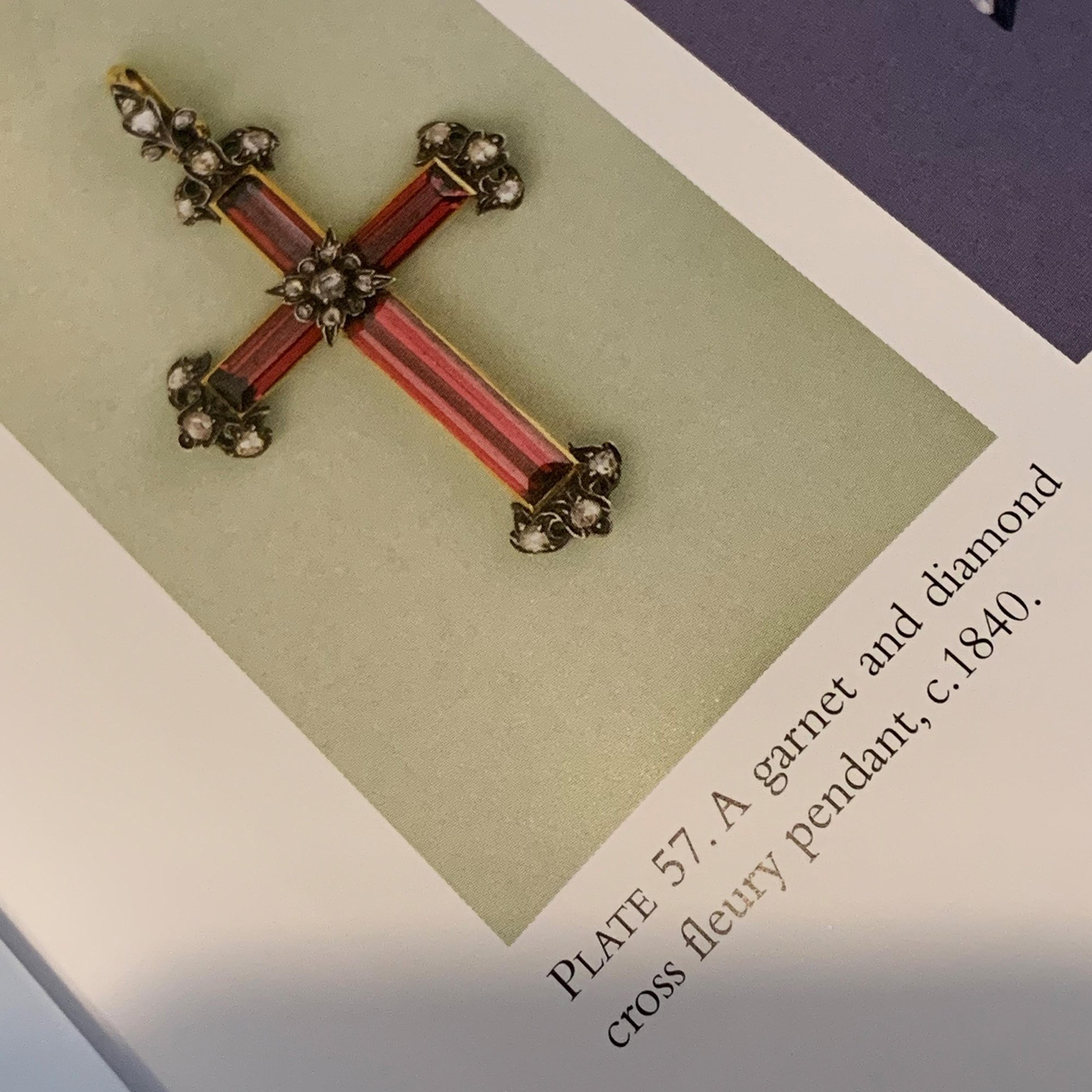

This exceptional and very rare pendant dates to the early Victorian period. This style of cross is known as a "fleury cross," so named for the petaled elements at the end of each arm of the cross inspired by the fleur-de-lis (or lily). It was often used as a symbol of the resurrection. The three petals of the fleur-de-lis can also be interpreted as a representation of the father, son, and holy spirit; or when used in heraldry, the fleury cross represents the virtues of wisdom, faith and chivalry. This outstanding example employs garnets (yes, those are garnets!) as the body of the cross around which is coiled a diamond-studded snake with ruby eyes and a forked golden tongue. In Christianity, the serpent is not only a symbol of chaos and evil but also of fertility, life and healing. The reverse side is embellished with engraved flowers and scrollwork. A similar, and dare I say slightly less impressive, fleury cross is referenced in the excellent jewelry reference book Understanding Jewellery by Daniella Mascetti and David Bennett. Hangs from a later Victorian 32" 9k gold chain.

thedetails

- Materials

15k gold, silver, garnets, 48 rose and old mine cut diamonds (1.25ctw), 2 1mm ruby cabochons, 9k yellow gold chain

- Age

c. 1840 cross, c. 1880 chain

- Condition

Excellent

- Size

2" length, 1.25" width, 32" chain

Need more photos?

Send us an email to request photos of this piece on a model.

Aboutthe

VictorianEra

1837 — 1901

The Victorians were avid consumers and novelty-seekers, especially when it came to fashion, and numerous fads came and went throughout the 19th century. In jewelry, whatever fashion choices Queen V. made reverberated throughout the kingdom. The Romantic period reflected the queen’s legendary love for her husband, Albert.

Jewelry from this period featured joyful designs like flowers, hearts, and birds, all which often had symbolic meaning. The queen’s betrothal ring was made in the shape of a snake, which stood for love, fidelity, and eternity. The exuberant tone shifted after Prince Albert passed away in 1861, marking the beginning of the Grand Period. Black jewelry became de rigeur as the Queen and her subjects entered “mourning,” which at the time represented not just an emotional state, as we conceive of it today, but a specific manner of conduct and dress. She wore the color black for the remainder of her life, and we see lots of black onyx, enamel, jet, and gutta percha in the jewelry from this time. Finally, during the late Victorian period, which transitioned along with a rapidly changing world into the “Aesthetic Movement”, there was a return to organic and whimsical motifs: serpents, crescent moons, animals, and Japonaisserie designed for the more liberated “Gibson Girl”. During the second half of the 19th century, America entered the global jewelry market, with Tiffany and Co. leading the way. Lapidaries continued to perfect their techniques, and the old European cut emerged toward the end of the Victorian period. The discovery of rich diamond mines in South Africa made the colorless stones more accessible than ever before.