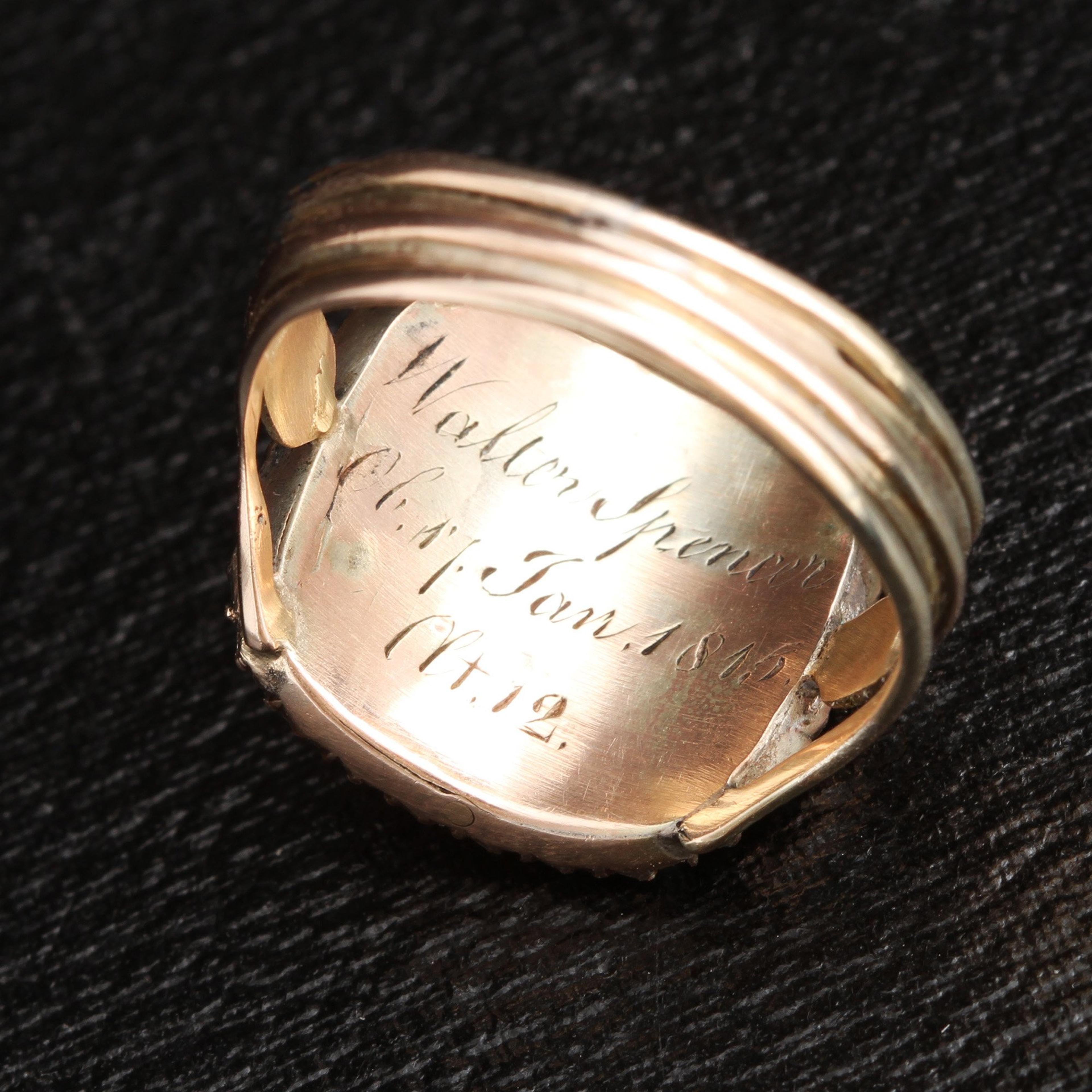

One of our favorite passages relating to the use of hair in 19th century mourning jewelry comes from Godey's Lady's Book of 1860: "Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look to heaven and compare notes with angelic nature, may almost say: 'I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now.'" This sentiment is all the more poignant when the jewelry in question memorializes a child. This beautiful mourning ring for Walter Spencer, who died at the tragically young age of 12, features and black and white enameled face with a weeping willow over a mausoleum. The black tomb houses a hair locket with a "WS" cipher and the mourning scene is framed by halo of seed pearls. The reverse side is engraved, "Walter Spencer Ob 17 Jan. 1815. Aet. 12."

thedetails

- Materials

10k yellow gold (tests), seed pearls, black and white enamel, hair locket

- Age

Dedicated in 1815

- Condition

Very good - minor surface wear commensurate with age and use

- Size

9.75, can be resized for an additional fee of $90' 7/8 x 5/8" head, 4.4mm shank

Need more photos?

Send us an email to request photos of this piece on a model.

Aboutthe

GeorgianEra

1714 — 1837

As imperialist war raged in the Americas, Caribbean, Australia, and beyond, the jewelry industry benefited: colored gems from all over the empire became newly available. A mix of artistic influences from around Europe contributed to the feminine, glittering jewels of the era. Dense, ornate Baroque motifs from Italy showed up in Georgian jewelry, as did French Rococo’s undulating flora and fauna. Neoclassical style made use of Greek and Roman motifs, which were newly popular due to the recently uncovered ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Lapidary methods improved: the dome-shaped rose cut was popular, as was the “old mine cut,” a very early iteration of today’s round brilliant cut.

The boat-shaped marquise diamond cut was developed around this time, supposedly to imitate the smile of Louis XV’s mistress, the marquise de Pompadour. Paste — an imitation gemstone made from leaded glass — was newly developed in the 18th century, and set into jewelry with the same creativity and care as its more precious counterparts. Real and imitation gems were almost always set in closed-backed settings, lined on the underside with thin sheets of foil to enhance the color of the stone and highlight it's sparkle. This makes Georgian rings tough for modern women to wear, especially on an everyday basis: genteel, jewelry-owning ladies of the 18th century were not famous for working with their hands like we are. Nor did they wash their hands as much as we do. Water will virtually ruin a foiled setting, so take special care with your Georgian ring. Very little jewelry from this period is still in circulation, and it's very difficult to repair.